Christ Church Cathedral Grafton

Christmas Eve

24 December 2018

[ video ]

Well, here we are …

In the middle of the night—when we should all be tucked up in bed—we are sitting in the Cathedral and celebrating the birth of a Jewish baby born in a very small village in Roman-occupied Palestine just over 2,000 years ago.

It’s a birth story

Like every other birth, the arrival of Mary’s boychild was an occasion of joy, accompanied by a sense of awesome responsibility, and profound hope.

Like us, as Mary and Joseph held their newborn baby in their arms, they must have wondered what life would be like for this wee fellow in the years ahead.

What would he be like? What gifts would he have? How would the people of the village and the wider family welcome this new person into their circle. Would he be famous? How would he make the world a better place? What can we do as parents to ensure he becomes all that God intends him to be?

Those are questions we have all asked ourselves as we hold newborn children in our arms.

The families who bring their children for Baptism in the Cathedral have similar thoughts in their minds and similar hopes in the hearts.

It’s the birth of Jesus

At Christmas we celebrate the birth of a most remarkable person.

Today the focus is on his birth. He was a real person. He arrived in this world the same way we all do. Incarnation. God taking flesh and entering into the stuff of this blue planet.

From small beginnings in a village in Palestine, not far from the palaces of kings and wannabe rulers, this vulnerable infant developed into an adult of courage, vision and passion.

This is not the time to talk about his death. Today we celebrate his life: his birth, his childhood and his ministry as the prophet of God’s active presence among us. Emmanuel. Through the life of Jesus God was active in our world, reconciling all things to himself and inviting us to embrace life.

Although Mary and Joseph could not imagine what was to come, this child was to have a huge impact all around the world, and during the past 2,000 years millions of people have been touched by his life and have reflected on what it all means.

In music, art, architecture, literature and compassionate action people who have been touched by Jesus has made their response to the deepest message of Christmas: Emmanuel.

God is not far away. God is here among us, within us and between us—as Jesus himself would say.

Christmas shows us where to look for God: right here and among our own circle of people we know best.

This is a simple idea, but it is also a very big idea.

It changes everything.

It is worth getting up in the middle of the night to celebrate!

Thin people

The child whose birth we celebrate tonight grew to become a person of the Spirit, a holy person.

When we talk about holy places, we sometimes describe them as ‘thin’ places; places where it seems the gap between our reality and the deeper reality of God has all but vanished.

We might also describe Jesus as a ‘thin’ person.

He most likely was physically thin, due to the diet of Jewish villagers in ancient Palestine and the active lifestyle of someone walking from place to place across Galilee. But I am referring to something else: his capacity to transform people.

What changed people was their discovery that when they met Jesus they also encountered God.

Jesus proclaimed the coming of God’s rule.

Jesus himself was the arrival of God, present among us in a new way. Emmanuel.

In the Gospel of John this mystery is expressed in words put onto the lips of Jesus by the later tradition: “Whoever has seen me has seen the Father.” (John 14:9)

Christmas invites us to embrace the possibility that our world is really a crowd of thin people.

Others encounter God when they meet us, and we encounter God when we meet them. Emmanuel.

Of course, this also means that how we treat others is also how we treat God.

Jesus said exactly that in his parable of the last judgment. The punch line for that story is: “When you did this (or failed to do this) for another person, then you did it (or failed to do it) to me.” (Matt 25:31–46)

If we embrace that possibility in the year ahead, then our lives and our world may well be transformed.

Christmas time is an opportunity to practice how we want to act for the rest of the year. This is a time when we naturally focus on things like:

- Community

- Generosity

- Compassion

- Love

When we make those things central to our lives, then we are transformed, the people around us are touched, and the world draws closer to God’s dream for us all.

May that be our experience this Christmas and throughout the year ahead.

Happy birthday, Jesus

Happy Christmas, Grafton.

Happy 2019, world!

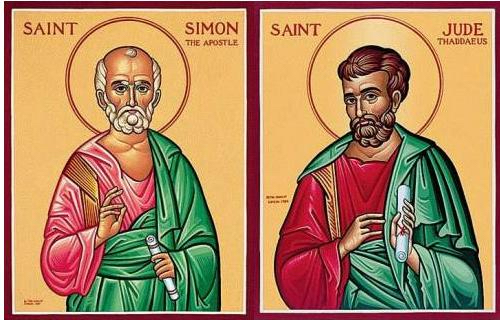

We can never be one of the Twelve, but we do have something in common with Simon and Jude: we are disciples of Jesus.

We can never be one of the Twelve, but we do have something in common with Simon and Jude: we are disciples of Jesus.

You must be logged in to post a comment.