A sermon for the feast of St Luke at St Mary’s in Exile, South Brisbane (18 October 2015).

Special readings chosen for the liturgy:

First reading: Luke 1:1-4

Psalm: Magnificat

Second Reading: Acts 2:38-39,41-47

Gospel: Luke 4:14-19

The gathering prayer:

God beyond all names,

we have heard the story of our ancestors journey of grace,

and we catch glimpses of that grace in our own lives.

Grant us eyes to see clearly,

hearts filled with compassion,

and strong hands to work for your justice;

in the name of Jesus. Amen.

The blessing prayer:

May our eyes see clearly,

our hearts overflow with compassion,

and our hands be strong to work for justice

this week and all weeks.

Introduction

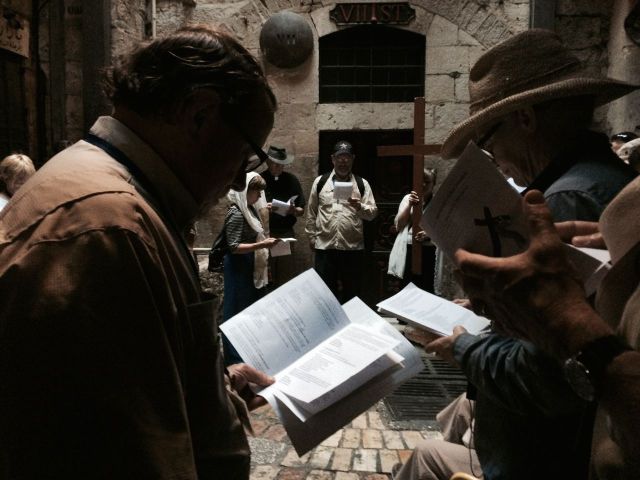

In traditional liturgical communities across the city and around the world people will be observing today as the feast of St Luke. That is not a custom that has survived in our exile from the church up the road, but today I invite you to join with me in giving attention to this special day.

On this day one can expect to hear sermons about the legacy of Luke. We owe to his literary imagination the cycle of the Church Year.

Some preachers and pew sheet editors will venture to tell people that Luke was a gentile medical doctor from Antioch in Syria and a companion of Saint Paul.

Others will extol his value as the primary historian of early Christianity, while others may talk about his excellent Greek language skills. He had the best Greek of any of the people who contributed to the New Testament.

In some places the preacher will focus on theological themes in the double volume of Luke and Acts which we attribute to this otherwise unknown author. Worshippers will hear about Luke’s interest in the Spirit, his respect for women, his concern for the poor, his preservation of major parables, and his interest in the wealthy.

Others will reflect on the significance of Luke’s Gospel being followed by a second volume, known to us as the Acts of the Apostles.

Again, for some people, the big news is that Luke was (supposedly) a companion of Paul and in some ways his biographer.

We are not going to do any of those things here today.

Reimagining Luke

We know nothing about the person who composed the Gospel of Luke and the Acts of the Apostles, except for what we can glean by close attention to these two books.

Together they comprise almost 25% of the New Testament.

With another 25% of the NT coming from the Pauline letters, and since “Luke” (as we call this anonymous author) was a serious fan of Paul, we can see that the Pauline faction in early Christian dominates the New Testament.

Paul’s legacy was not always so esteemed in earliest Christianity, and his heavy imprint on the New Testament may be largely due to the work of people such as Luke.

For most of the last 2000 years Luke has been seen as a companion of Paul, but that is no longer a viable option. More likely, Luke comes from the generation after Paul; or even the generation after that.

The opening paragraph of Luke’s Gospel (1:1–4) which we heard as the first reading is one of the few places where Luke speaks in his own voice. He tells us that he has a purpose in writing. He has a method. And he has sources, because he can access the earlier written works created by those who went before him.

That pushes Luke back to a period after 100 CE, and perhaps as late as the middle decades of the second century.

A sermon is not the time or place for a lecture on the dating of Luke’s two great literary works, but I invite you to think about the significance of Luke writing to meet the needs of the church in his own time about one hundred years after Easter.

The diverse and still marginal Christian communities at that time faced two major challenges.

The external challenge was the power of the Roman empire and especially the ongoing tensions between Rome and the Jews, with rebellions and uprising in the late 60s, the 80s, 115–117 and 132–135 CE. The Christians were caught between a desire to operate under the legal protection of being a Jewish sect, and the need to demonstrate to Rome that they were not a strange bunch of Jewish rebels. Having a leader who had been executed as a rebel was not really a good marketing strategy for that time and place.

The internal challenge was a rising tide of Christian anti-Semitism, especially associated with a church leader called Marcion. Marcion proposed that Christians jettison all vestiges of their Jewish legacy. He rejected the violent and tribal God of the Old Testament, and he proposed a new Bible that comprised simply The Gospel (traditions about Jesus) and The Apostle (the letters of Paul).

Marion’s ugly ideas found a ready hearing in a context where it was good politics to demonstrate loyalty to the Empire by denouncing Jews. Had his ideas won the day, Christianity would have been even more anti-Semitic than it would soon become, as it often has been, and in some expressions remains to this day.

Luke and Marcion were both fans of Paul.

They probably both misunderstood and misrepresented Paul.

But Luke rescued Paul from Marcion and promoted a vision of Christianity that valued its Jewish past while claiming a place in the social order of the Roman empire.

Luke valued the past, understood the present, and forged a path into the future.

His legacy has shaped Christianity for much of the last 2000 years.

Luke’s legacy

I want to suggest that Luke’s offers an attractive template for us a community in transition.

To unpack that idea I need to divert to Matthew ever so briefly. Bear with me.

In Matthew 13:52 we find this short but powerful parable:

“… every scribe who has been trained for the kingdom of heaven is like the master of a household who brings out of his treasure what is new and what is old.” (NRSV)

While Luke did not know, or at least did not preserve, this parable of the scholar prepared for God’s kingdom, he certainly seems to fit the description very well.

Luke was a scribe trained for the kingdom of heaven.

Luke delved into his sources to find just what was needed for his own time.

Luke valued the past but critiqued the traditions. He thought he could present a more accurate account than any of those who had gone before him; including, I suggest, Matthew, Mark and John.

Luke was not afraid of creating new traditions, and refashioning older traditions, to serve his purposes and to meet the needs of the church in his time.

Luke invites us to assess the traditions we have inherited and start all over afresh.

Luke does not ask us to discard everything from the past, but he does invite us to catch a fresh glimpse of the God who feeds the hungry and overthrows the powerful.

Luke was convinced that God is at work in the world for good, and he invites us to see where God is at work now and join that that project ourselves.

For all these reasons we can celebrate Luke today. Amen.

You must be logged in to post a comment.