Lent 5C

St Paul’s Church, Ipswich

6 April 2025

[ video ]

As I mentioned earlier, today we change gear and move into a lower worship tone, as it were. Until recent times, in many churches today would have been called Passion Sunday, two weeks before Easter, a week before Palm Sunday.

As you may remember, the little purple sacks would magically appear from the flower vestry and then cover everything that was too celebratory. The cross above the Altar, the processional cross, the cross on the wall in the western sacrament chapel and so on. And it’s just one of those little customs that developed and then—sort of it like nut grass—got away on us, so it’s being pulled back under control. The idea was that as we got closer to Good Friday, we would cover all the bejewelled and glorious decorations in the church, and particularly empty crosses, which, of course, represent resurrection. But once people got the idea of putting little purple sacks over things there was no stopping them, and anything in the church that could be covered was draped in purple. I was fortunate never to have a purple sack put over myself.

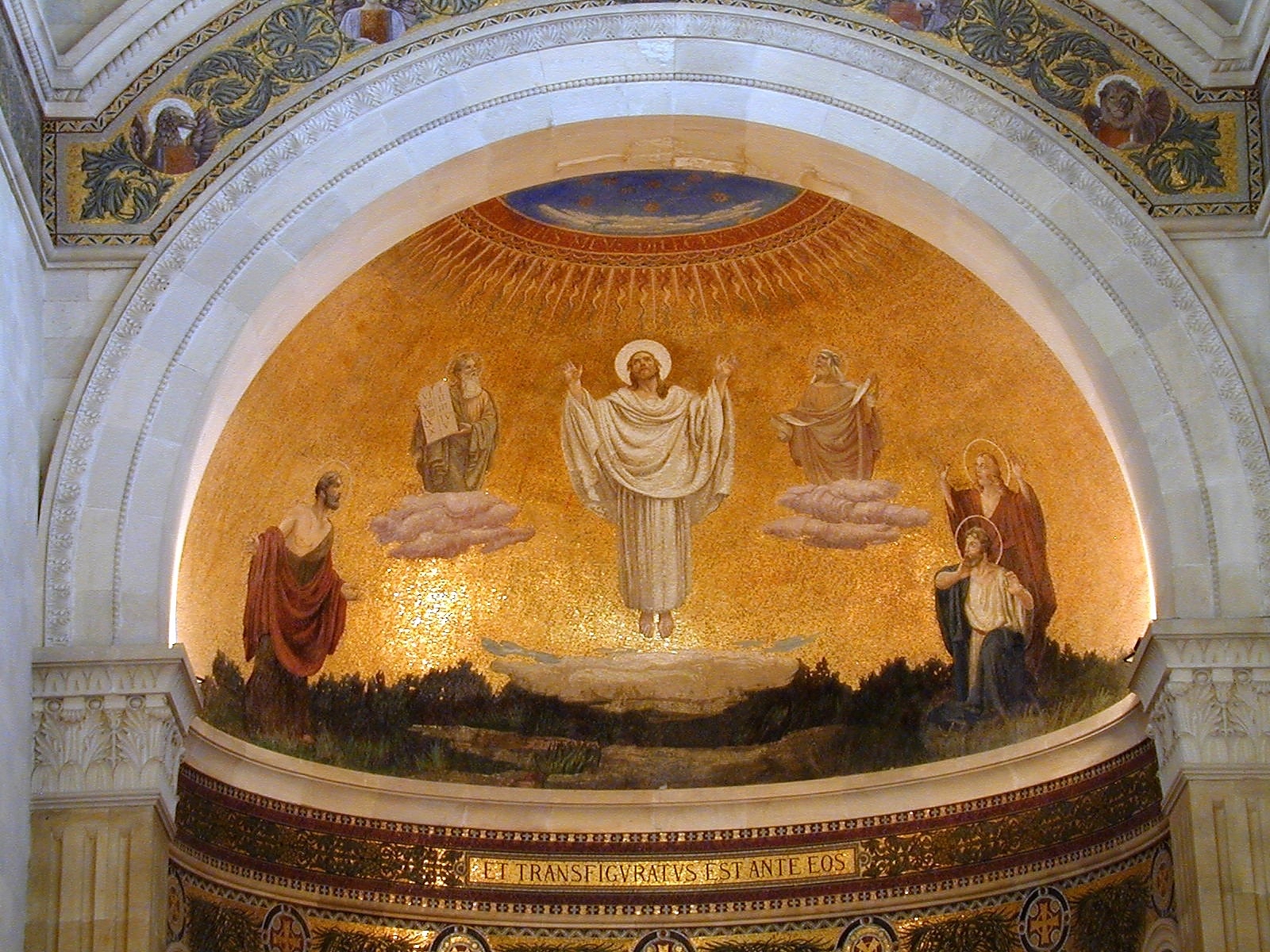

So we’ve changed somewhat in how we observe these festivals, in the more recent liturgical thinking. I note with delight that the incoming Rector teaches liturgy at the College of the Transfiguration in South Africa. I’m just a simple biblical scholar, but Mpole is a liturgical scholar. So we’re about to get some really well-thought out liturgical leadership in the life of the parish, which will be a great blessing. I shall watch it with pleasure from afar.

Today, we’ve got this beautiful, fascinating, and delightful story is surely one of my favourite stories from the Gospels. It must have been a favorite in ancient times as well, because there’s a version of this story in each of the four gospels. It occurs in Mark, the earliest gospel and it occurs in Matthew, which is an expanded edition of Mark. It occurs in Luke, although for some reason, Luke relocates the story up into Galilee at an earlier point in the narrative. And as we heard, it occurs in John. There are not many stories that occur in all four Gospels, and this is one of them. It’s even more unusual because it’s a story where a woman is the central character.

That makes it unusual in the Bible as well. You might remember even last Sunday, Mothering Sunday, we had the story of the prodigal father, because there was not a story about a loving mother that could easily be read from the Gospels.

So we have this story which is set in what was then the village of Bethany. Bethany is on the other side of the Mount of Olives. One side of that ridge faces towards Jerusalem, the other side faces towards the desert, and that’s where the little village of Bethany was. It appears to have been Jesus’ safe place whenever he came to Jerusalem. That, by the way, makes the story a bit odd, because the best we can tell, Jesus was already staying at Mary and Martha’s house. He didn’t just turn up there in the way this passage suggests today.

There are two interesting things about that location. Firstly, the 40,000 or so local Palestinians who live there and—of course—speak Arabic, do not call their village Bethany. Rather, they call it el-Azariyya, Lazarus town.

Two thousand years on, they’re still remembering the story of Lazarus. I guess it’s the biggest thing that’s ever happened in Bethany. So the local people still know their village as el-Azariyya, the home of Lazarus.

The sad thing about Bethany these days is that it has the misfortune to be right on the cusp of the so-called green line or at least the apartheid wall, which Israel has built between its own territories and the West Bank. It’s in what’s called Area C under the Oslo Agreement. Area A is supposed to be under Palestinian control, except when the Israelis want to go and get something. Area B is under shared control, and Area C is under Israeli control, but Bethany is just on the other side of the four-meter-high concrete wall which Israel has put through the middle of the Abu Dis village to divide Palestinians on one side of the street from those on the other side of the street.

So Bethany today is a kind of no man’s land. The Palestinian authority has no control because it’s in Area C and the Israelis don’t go there because they don’t care what happens on the other side of the wall. If you’re in trouble with the authorities today, Bethany is the place to be. It’s a wild west kind of town.

So Jesus comes to a Bethany, which was much smaller, much quieter, and in many ways offered him a safe haven. In just the previous chapter of John’s gospel, he’d already been in Bethany because he’d come to show his respect and his love for the family following the death of Lazarus

They had let him know that Lazarus wasn’t well, but he didn’t come straight away. In chapter 11, he delayed a few days, and by the time he and the disciples got to Bethany, Lazarus had been dead several days. Martha, the tougher of the two sisters—remember Mary and Martha?—Martha gave Jesus a piece of her mind as he arrived. Why weren’t you here? Had you been here my brother would not be dead. And Jesus says something like chill, Martha, just chill. It’ll be okay. Wait. Watch.

So as the story goes on, Jesus calls Lazarus out of the tomb and restores him to life and restores him to his sisters.

The little household that we have there in Bethany is an interesting household. It’s a household comprised of two adult women and their brother, Lazarus, who often is not part of the story. In some ways, it really is Mary and Martha’s place and Lazarus seem to be there some of the time. So in today’s part of the story, Jesus has turned up for dinner at the home of Martha and Mary and Lazarus.

The little family of three adults is putting on a bang-up feast. Well, of course they are. Think about it. Just a few days earlier, Lazarus was dead and they were getting ready to host wave upon way of neighbours and family coming for the days of condolences, which also means wave upon wave of cooking for the people who are hosting visitors, who are coming to express their solidarity and their comfort to the bereaved family. That was the plan.

That was the expectation but now Lazarus is alive and Jesus is coming for dinner, and it’s going to be a bang-up celebration for sure, and the guest of honour … Well, is it Jesus, or is it Lazarus?

I mean, who are people coming to see when they come by Mary and Martha’s house? For sure they’ve heard about Jesus but I suspect they really wanted to see for themselves that Lazarus really is alive.

So Martha is busy. You might remember, that’s her role in these stories, Martha is busy serving, and it is Mary who is the more emotional sister here. I’m not going to say anything about my three sisters, because this is being live streamed. But many of you will have sisters, or be a sister, and you will know some sisters are very organized. They work from the head. Other sisters are very emotional, and they work from the heart. Mary is the second. She’s the one who is much more emotional. She’s the one who—in Luke’s story—sits by Jesus’ feet, listening to him while Martha is busy in the kitchen. So we know, we know this family, okay?

Mary took a pound of costly perfume, pure nard and which would have been in a little tiny bottle. If I had thought about in time, I could have actually brought one in from the collection at the college: a little glass bottle about so deep, full of precious ointment. She uses the ointment to anoint Jesus’ feet, and then she wipes off the excess ointment with her hair.

An interesting moment in the middle of dinner, I guess. But the point is, she is just so happy to see Jesus, that she can’t do enough for him. Where she might have been by preparing her dead brother’s body with ointment, she’s now massaging and anointing the feet of the one who brought her brother back to life.

And of course, there is the grumpy uncle, Judas Iscariot, sitting in the room. “What a waste of money. That item could have been sold for 300 denarii and the money given to the poor.” We all know people like that. Three hundred denarii, by the way, is basically a year’s wages to a worker: one denarius a day, so 300 denarii is pretty close to year’s wages.

That’s a lot of money. In our terms, it cost around $80,000 for that little jar of ointment.

But for Mary—and I suspect for Martha in her better moments—nothing was too expensive to express their gratitude to Jesus; whereas Judas just sees a waste of money.

Jesus’ comment is interesting.

Leave her alone. Get off her case. She bought this so that she might have it for the day of my burial.

And in saying that Jesus is connecting the events in the house of Mary and Martha and Lazarus with his own destiny on the cross in just a few days’ time, about a week later, according to the time signal at the start of today’s Gospel.

So I love this story, but I guess the point of this story, which has been playing around in my head during the week is, is the question of gratitude. How grateful are we for what God has done for us? In another version of this story in Luke’s Gospel, Jesus says to Simon the Pharisee, those for whom much has been forgiven, had much love to show.

Where is our gratitude? How aware are we of all that God has done for us? And where are the limits to our generosity, to our enthusiasm, to our love as we demonstrate our gratitude to God, the source of life and the source of our salvation? Amen.

You must be logged in to post a comment.