St Paul’s Church, Ipswich

Australia Day

26 January 2025

[ video ]

What a week to be preaching.

Every week the sermon is an awesome responsibility for any preacher. Some weeks the weight seems heavier.

This is one of those weeks.

Today we observe Australia Day.

That alone puts the preacher between a rock and a hard place. How does the gospel of Jesus connect with the reality of a society constructed on lands that were stolen from its ancient inhabitants?

How do we speak truth to power, or even simply to ourselves?

Meanwhile, this has been the week when a new administration comes to power in the United States of America, and we have seen the sparks fly as an Anglican bishop challenges the core values of the man now wielding immense power as his party controls both houses of Congress after he has previously stacked the US Supreme Court with conservative justices.

Let’s not even mention the coalition of oligarchs with wealth largely derived from their pervasive commercial technologies who have backed this man into power and now wait to reap their unjust rewards.

It seems that the mighty have climbed back onto their thrones. The lowly have been cast down once more. The hungry have been refused food. The alien and the strangers have been targeted for deportation. And the rich get richer by the day.

How do the readings set for this Sunday speak into these realities?

Nehemiah 8

Now that is a fascinating reading.

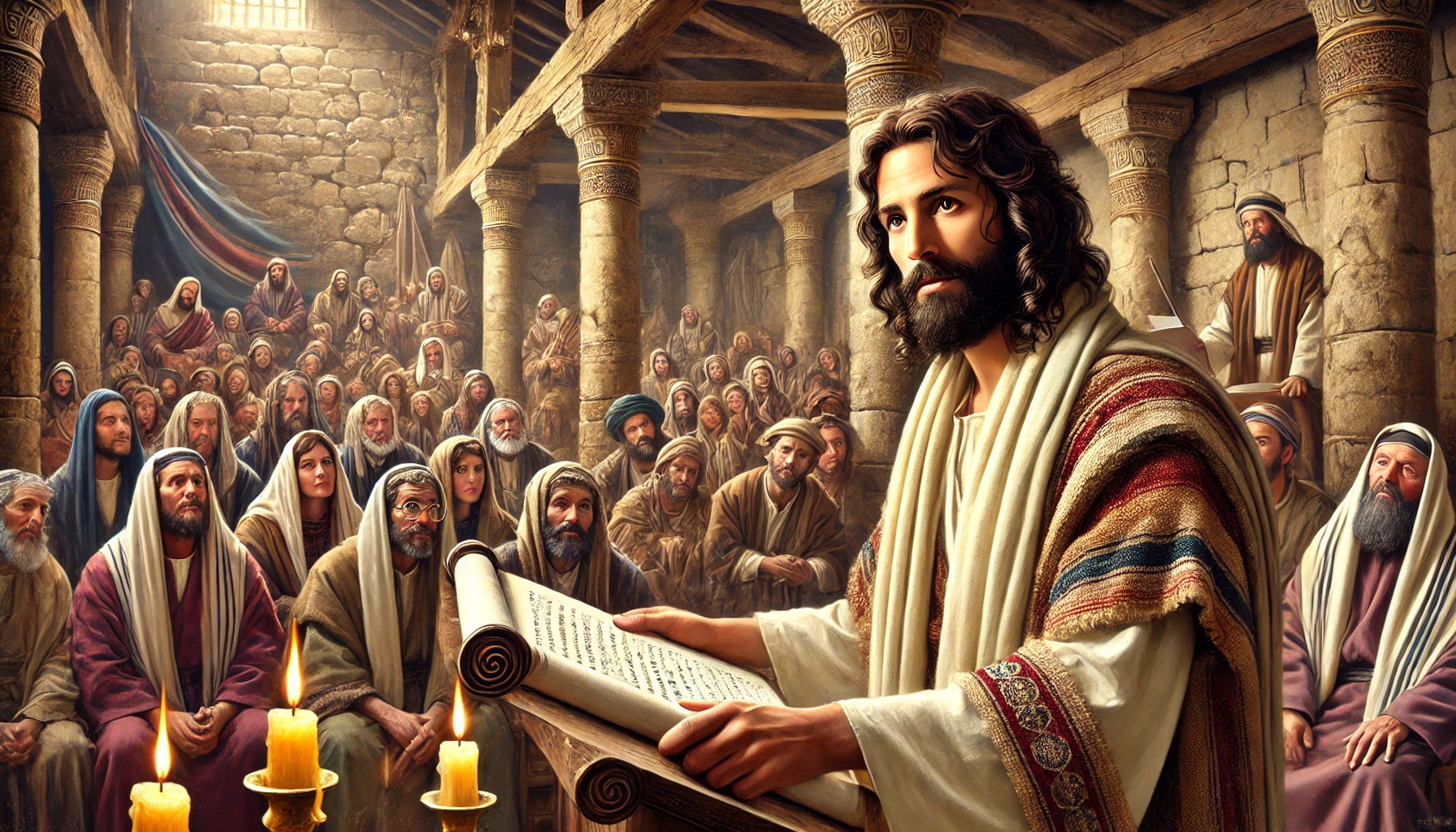

This is very first time we have a description of the Bible being read to an assembly of people by a professional Scripture scholar.

As the storyteller imagines the scene, the crowd cannot even understand the Hebrew language of the Bible, so it needs a simultaneous translation into Aramaic by a team of support teachers (the Levites).

Ezra stands at a podium on an elevated platform. We still do that some 2,500 years later!

This was no pious devotional exercise. Ezra was establishing the principle that the sacred scriptures of the Torah—the first five books of the Old Testament—formed the constitutional basis for the province of Yehud within the Persian Empire.

Let that little fact sink in.

The very first time we hear about the Bible being read in public, it was being used for politics.

So much for keeping religion out of politics, or politics out of religion.

Not that we ever have.

And these were nasty xenophobic politics, that justified the cruel deportation of residents who were deemed to be aliens and outsiders by the narrow-minded theological purists led by Ezra.

I am speaking of Jerusalem ca 400 BCE, not Washington in 2025.

Families were to be separated and torn apart, and the so-called foreign women—actually they were simply worshippers of God from the northern tribes rather than the southern tribe—were to be divorced and expelled; along with their children. These women were the grand daughters and great nieces of Elijah and Elisha, but that mattered nothing to the conservative hardliners who wanted a society defined by purity; at least by their definition of purity.

The books of Jonah and Ruth may have been written to offer an alternative vision of God’s inclusive love, but the hardline policies of the right wing prevailed.

Then as now.

Luke 4

Meanwhile in today’s Gospel we have the famous inauguration scene—yes, you heard me correctly, the inauguration scene—where Jesus announces his program as the prophet of the reign of God. What a contrast with the inauguration charade in Washington this past week.

“The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, because he has anointed me to bring good news to the poor. He has sent me to proclaim release to the captives and recovery of sight to the blind, to let the oppressed go free, to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favour.”

And he rolled up the scroll, gave it back to the attendant, and sat down. The eyes of all in the synagogue were fixed on him. Then he began to say to them, “Today this scripture has been fulfilled in your hearing.” [Luke 4:18–21]

As Luke tells the story, Jesus follows the ritual set in place by Ezra some 400 years earlier. He stood up to read, presumably at the bamah, or high place. What we would call a lectern or a pulpit.

Jesus finds the passage set for that day, perhaps following an early form of the Jewish lectionary. He highlights the prophetic words of the haftarah, the secondary text read alongside the Torah passage set for that Shabbat.

He says that the following words had been fulfilled in their hearing that very day, right there in the tiny synagogue of Nazareth:

“The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, because he has anointed me to bring good news to the poor. He has sent me to proclaim release to the captives and recovery of sight to the blind, to let the oppressed go free, to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favour.”

This was a message of hope, freedom, liberation, healing and divine blessing.

That, my friends, is the agenda of Jesus.

We find it elaborated in the Beatitudes from the Sermon on the Mount, which Luke preserves in this form:

“Blessed are you who are poor, for yours is the kingdom of God.

Blessed are you who are hungry now, for you will be filled.

Blessed are you who weep now, for you will laugh.

Blessed are you when people hate you, and when they exclude you, revile you, and defame you on account of the Son of Man. Rejoice in that day and leap for joy, for surely your reward is great in heaven; for that is what their ancestors did to the prophets.

But woe to you who are rich, for you have received your consolation.

Woe to you who are full now, for you will be hungry.

Woe to you who are laughing now, for you will mourn and weep.

Woe to you when all speak well of you, for that is what their ancestors did to the false prophets.” [Luke 6:20–26]

The good news of Jesus is not for those who are doing just fine in the present system, thank you very much.

That point is made very clear in Luke’s version of the Lord’s Prayer, which of course the church has never asked us to learn by heart so we can recite it together when we gather at the table of Jesus:

Father, hallowed be your name. Your kingdom come. Give us each day our daily bread. And forgive us our sins, for we ourselves forgive everyone indebted to us. And do not bring us to the time of trial. [Luke 11:2–4]

The message of Jesus and therefore our message to the Commonwealth of Australia is to promote a vision of liberation and empowerment for the oppressed and the dispossessed.

We do not back one party over another. They have all failed to embrace the radical vision of Jesus Christ.

But we do speak truth to power, and sometimes that begins by speaking truth to the person we see in the mirror.